|

|

Impacts of exchange

rate policies (page 401)

In what ways does a

country's exchange rate policy impact on the following:

-

Businesses

within its borders which carry out international transactions?

-

Foreign trading

partners?

-

Investors (both

foreign and domestic)?

|

|

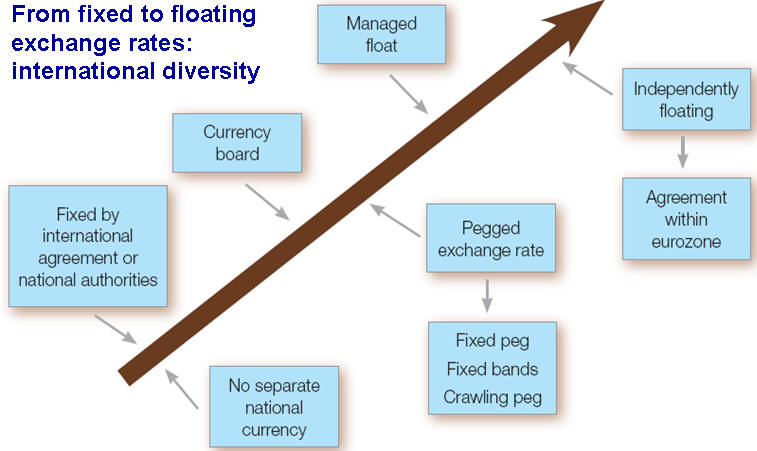

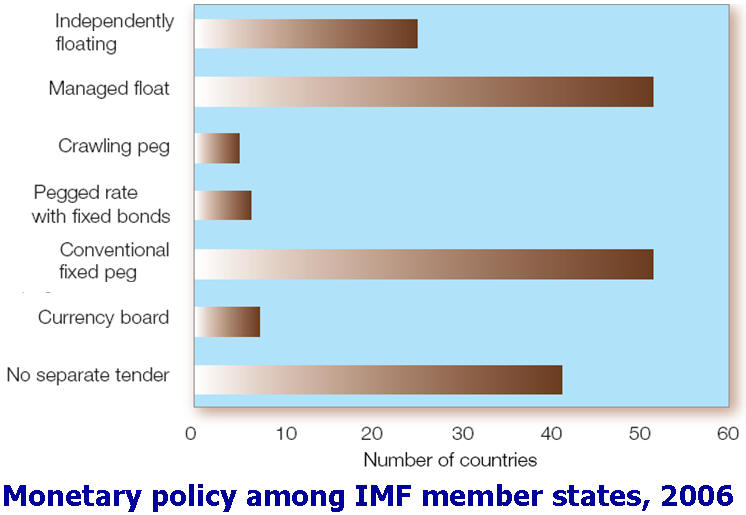

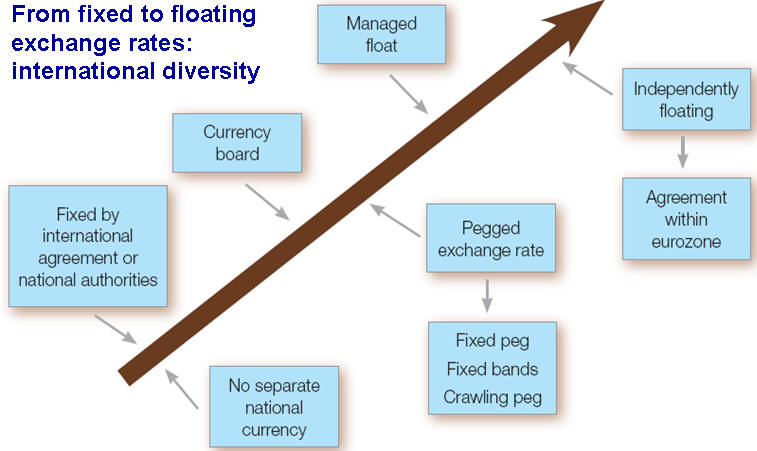

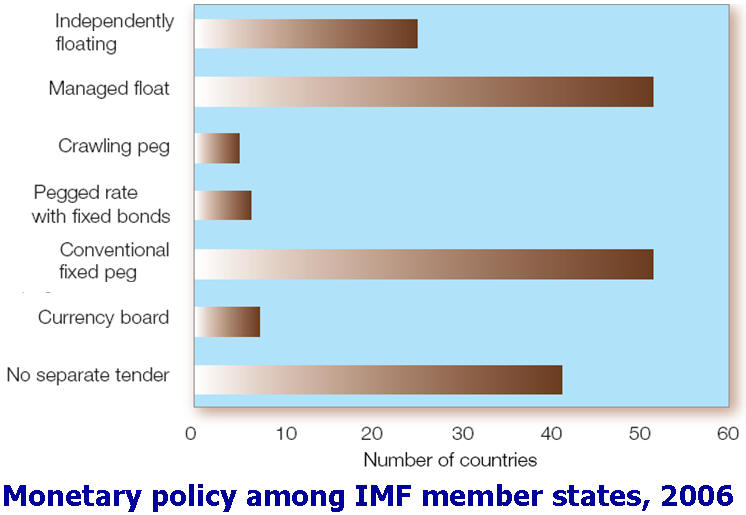

It is helpful first to

summarize different

exchange rate policies operated by different

governments. As

these two graphs

show, they range

from fixed to the

various types of

floating rates.

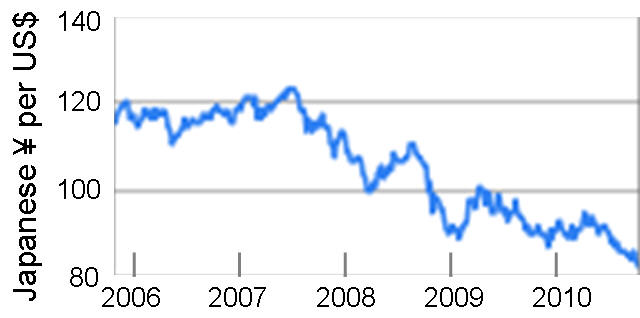

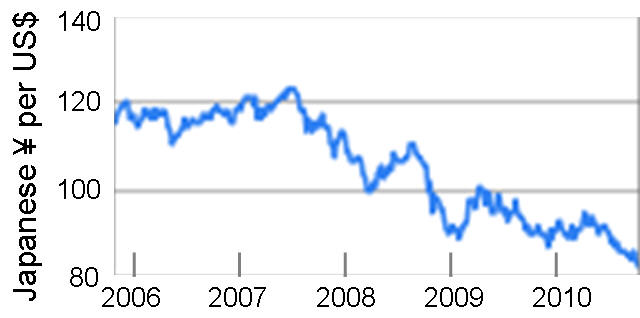

The effect of domestic interest rates and

inflation rates on spot and forward exchange rates can be

envisaged as follows. Suppose the domestic interest rates are

r¥

in Japan and r$ in the US. Also assume that the

corresponding inflation rates in Japan and the US are i¥

and i$, respectively.

|

|

Now, as the primary responsibility of a country's

central bank is to guard against inflation, and setting the correct

interest rates is the basic mechanism for doing so, these two rates can

be taken to have the same effects over time. For instance, if the annual

interest rate in the US is 5% (i.e.,

r$

= 0.05) then a deposit of $100 at this rate today will become $105 after

one year. Likewise, if the Japanese annual interest rate is <2% (i.e.,

r¥

= 0.025) then

¥100

deposited today at this rate will become

¥102

after one year.

The following are the

impacts that a country’s exchange

rate policy has on

the different businesses, trading partners and the investors:

-

Businesses within its borders

which carry out international transactions

– The fixed exchange rate

offers certainty to these businesses, but it might be set at a rate

which is not particularly favorable for the individual business. It

if is set low, exporters benefit, but if it is set high in relation

to market perceptions, exporters will feel disadvantaged. A floating

exchange rate subjects it to market forces. This could seem

preferable, but much depends on market perceptions: if the currency

is strong, exporters may not be so happy.

-

Foreign trading partners

– Foreign trading

partners are sensitive to the possibility that a government may wish

to see its currency undervalued, and this may create trade tensions.

Governments can use the policy of devaluing the currency, which

helps domestic businesses, but disadvantages foreign trading

partners.

-

Investors, both foreign and

domestic –

Investors committing themselves to FDI projects wish for stability

in exchange rates, so that they can plan ahead with confidence.

However, portfolio investors may be short-term in their outlooks,

and may simply look for financial gains. The opening of capital

markets around the world has left many countries vulnerable to

speculative activity, which can affect their currencies. Those

pegged to the dollar were vulnerable in the Asian financial crisis.

Where the currency is allowed to float, volatility is especially a

risk in a small, open economy. Governments do intervene to prop up

the currency, but this is seldom effective.

|

Globalization and

stock markets (page 410)

Contrast the stock

markets described in this section in terms of their

internationalization. Assess the extent to which stock markets at

present are indicative of globalization trends or, alternately, more

local factors. Give examples.

|

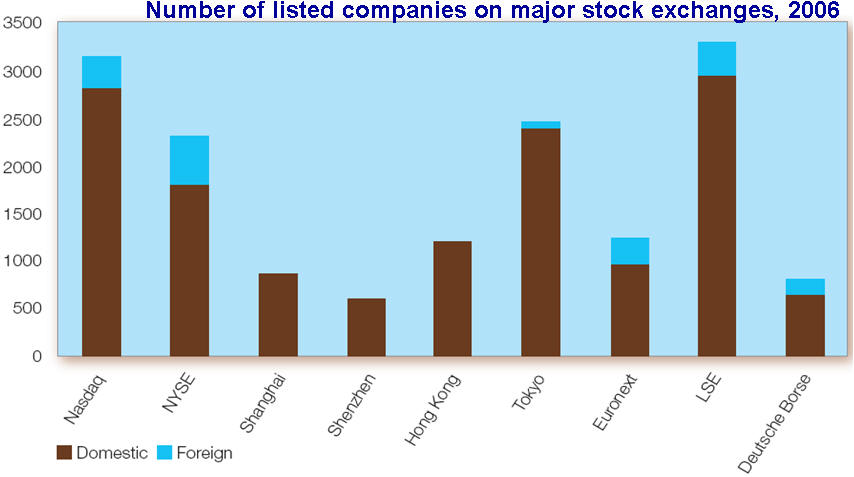

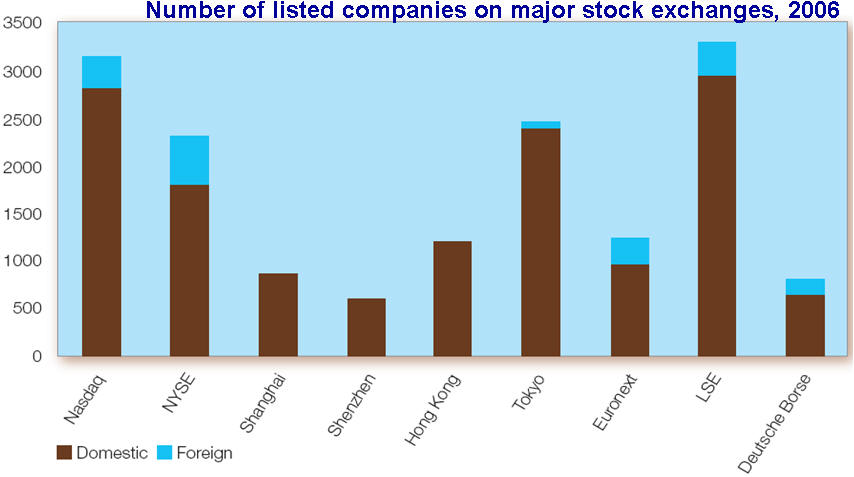

Stock markets become internationalized as more

foreign companies list on them through IPOs. Investors also indicate

international appeal if they invest in stocks listed on exchanges other

than their own. The extent of internationalization of an exchange

depends heavily on the regulatory framework of the exchange. Exchanges

are all overseen by regulators associated more or less closely with

their national governments. The law in some countries does not allow

foreign investors or foreign companies to list. As shown in the figure

below, the Chinese exchanges do not allow foreign companies to list. The

most internationalized are American and European exchanges.

Japan attracts few foreign listings. The stock

market is indicative of the extent of globalization in the country’s

financial system. London as a financial centre has become highly

globalized, attracting listings from companies in large emerging

markets, such as Kazakhstan and Russia.

Some exchanges, such as the Dubai one featured in

CF 11.2, aim specifically to attract foreigners. One means has been to

set up a regulatory framework similar to that in the UK. This has not

been entirely successful: local companies, accustomed to rather opaque

governance, were reluctant to sign up to a system which did not accord

with their way of doing things, and foreign companies were perhaps

dissuaded by the local cultural and political environment (as well as

the newness of the exchange). Thus, both local and global factors play a

part. Some of the exchanges in emerging markets, such as India, China

and Russia, have been very volatile. They have risen dramatically, only

to fall equally dramatically, suggesting that they have not yet reached

the maturity which would assure foreign investors.

|

Corporate finance alternatives

(page 415)

Assess the available means of

raising capital, together with their benefits and drawbacks, for the

following companies:

|

|

|

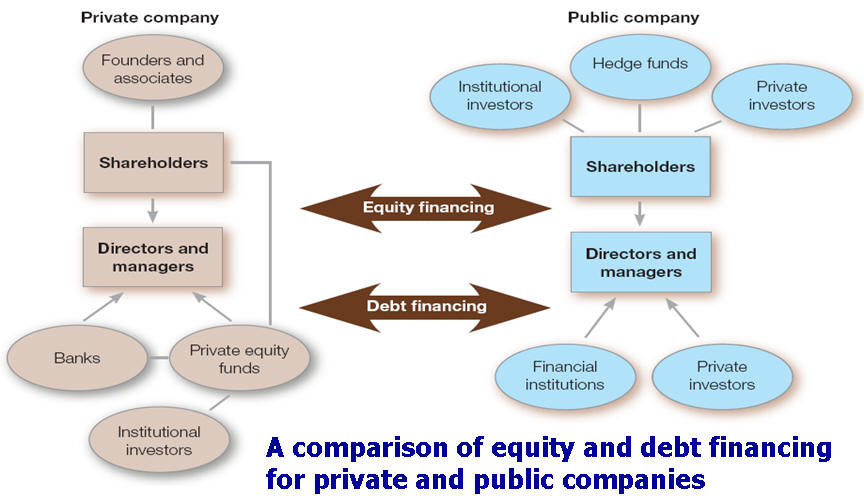

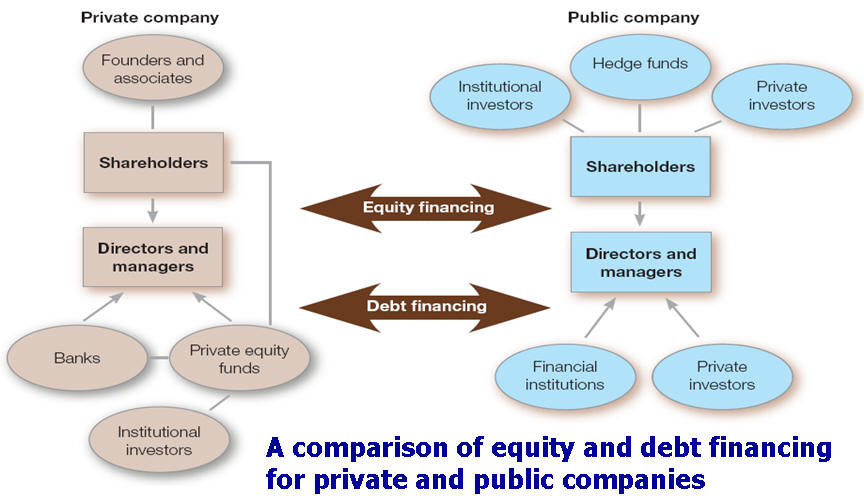

Debt and equity

financing

Corporate preferences for

debt or equity financing are linked to ownership and governance

structures in national environments. In economies with open

markets for shareholder participation and control, equities are

a favored way of raising capital, whereas in more closed, more

narrowly controlled market, debt financing is preferred, usually

through banks. Private companies, especially SMEs, have fewer

capital-raising options than public companies; their shares are

not traded, and debt financing is more limited. |

This company has limited

means of raising money. It is funded by the insiders who are its

shareholders. It can seek bank loans, but these are sometimes

difficult to obtain, especially during a credit crunch. Raising

finance could therefore be difficult. This type of company often

seeks help from venture capitalists who recognize the potential in

the business.

-

The large public company with

subsidiaries in many countries

–

This company probably has numerous shareholders. At least a portion

of its shares are freely traded. It could be the major shareholder

in its subsidiary companies, which are registered in the countries

where they are located. The parent company can raise capital by

equity issuance, and by loan capital (the issuing of debentures).

|

Winners and losers in

battles for corporate control (page 418)

Takeover situations

can be viewed from a number of different perspectives. What issues

are raised for each of the following groups, and how likely is each

to gain from a takeover?

-

Shareholders of

the acquiring/acquired company.

-

Managers of the

acquiring/acquired company.

-

Employees of

the acquiring/acquired company.

|

Winners and losers in takeover situations:

Shareholders

– Shareholders are concerned

about the value of their shares, their voting power, and their voice in

the company. Shareholders of the acquiring company can expect to see

their shares fall in value as a rule, and shareholders of the company

being acquired see theirs rise. The reasons for the fall in the

acquirer’s shares are that the shares will be diluted with the influx of

new shareholders, and the risks involved could well impair performance,

at least in the short term.

Managers

– Managers are concerned about

changes of strategy and structure, which are often entailed in a

takeover. Those in the acquiring company may see opportunities for

themselves, but this would mainly be in takeovers where the new business

is in the same sector as the acquirer’s business. Managers in the

acquired company are likely to be fearful of losing their jobs – only

the best might be kept on. They might also be concerned about the change

of direction. Many managers in takeover target companies will leave,

unhappy about the uncertainties or simply because they do not want to

work for a company which is owned by another.

Employees

– Employees are concerned about

their jobs, any new roles, and place of work. Those in the acquiring

company are generally thought to be safer in their jobs than those in

the acquired company. Employees in the acquired company might be offered

a new job in a new location, but might not be happy with the upheaval.

Employees in the company taken over are usually vulnerable in this

situation. Their employment rights are protected in the EU by the

Transfer of Undertakings Regulations.

|

The good, the bad and

the risky (Page 423)

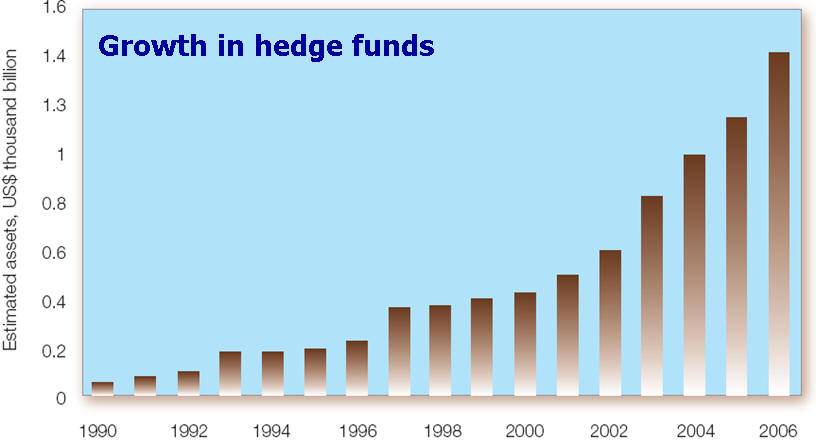

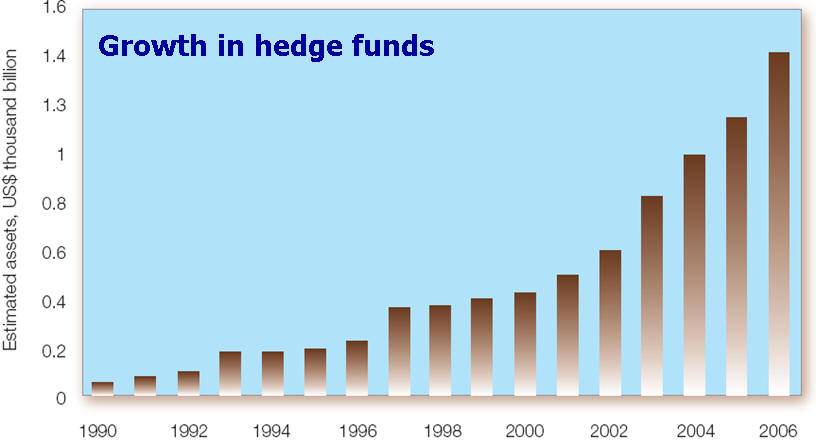

Hedge fund and

private equity fund managers argue that their active investment

strategies stir up complacent incumbent managers, acting as catalyst

to achieve better performance and long-term value creation. If this

represents the 'good', what are the 'bad' and 'risky' aspects of

their activities?

|

Aspects that might be considered ‘bad’

-

Hedge funds and private equity groups tend to

have short-term perspectives. They are mainly interested in gains

for their investors, rather than the interests of target companies.

-

The tactics of hedge funds are sometimes

considered dubious. They deal in derivatives such as share options,

and can build up positions without the company’s knowledge. They

also have a poor reputation for going ‘short’ on shares, in the hope

they will fall in value.

-

Private equity groups typically use debt

financing to finance their buyout activities, building up the debt

burden on target companies.. This creates a huge burden, as the

Debenhams example shows.

-

Restructuring often entails job losses in the

target company. This could be seen as good, but not from the point

of view of the person who has lost a job. By contrast, the private

equity buyout partners reap huge rewards from their activities, many

of which have successfully exploited tax loopholes.

Aspects that might be considered ‘risky’

-

Hedge funds and private equity groups have

relied on the availability of loans at advantageous rates. Any rise

in interest rates or reduced availability of loans (the credit

crunch) dramatically affects their business model.

-

Weak accountability and lack of regulation

creates risks in the operations of hedge funds and private equity

groups. Financial crisis in late 2008 seriously affected both.

Existing investors wanted their money back, and new investors were

in short supply.

|

IFRS and beyond

(page 430)

What trends are evident in the

changing regulatory environment, which impact on MNEs? To what

extent are these changes constraints on their activities or

beneficial in their value-creating activities?

|

|

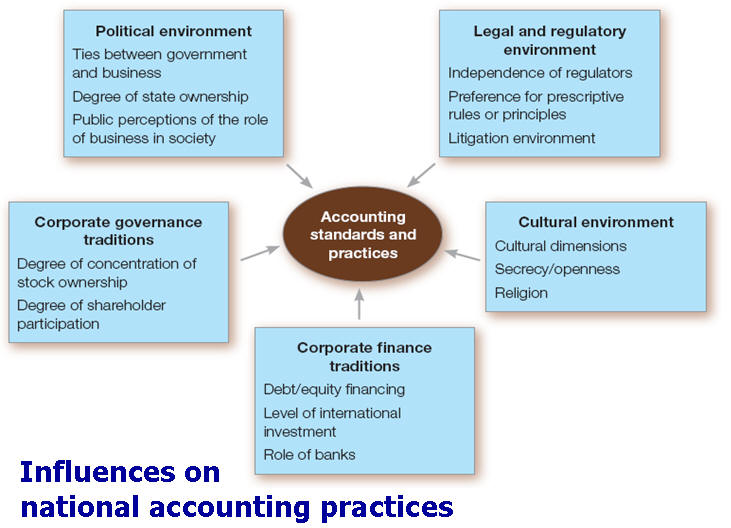

IFRS rules are designed to harmonize accounting

standards, and also to make firms present a more accurate and

informative picture. For companies which have in the past used practices

which give a rosier picture than would be presented under the new rules,

the new standards represent a constraint.

An example is the treatment of

financial instruments, including derivatives. These must be measured at

fair value and included in the profit and loss account. The treatment of

leases, which involve long-term debt, must now reflect this reality,

rather than be treated simply as assets. |

|

Likewise, the cost of

employees’ benefits, including share options, must be disclosed, and

treated as operating expenses.

Following the collapse of Enron, the US

legislature passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. One of the concerns which

arose in the Enron case was the extent of special purpose entities,

which were kept off-balance sheet. The new law did not ban their use,

but revised the rules for disclosing off-balance sheet debt. Much of the

new law concerns compliance requirements for certifying accounts. CEOs

and chief financial officers became liable for certifying the company’s

accounts. Criminal penalties for reckless certification were increased.

The impacts on MNEs included increased costs of compliance with

Sarbanes-Oxley rules, which also applied to foreign companies listed in

the US. The US trend was to increase legal formalities, but many might

question whether this is effective: some companies will simply find ways

of getting round the law.

|

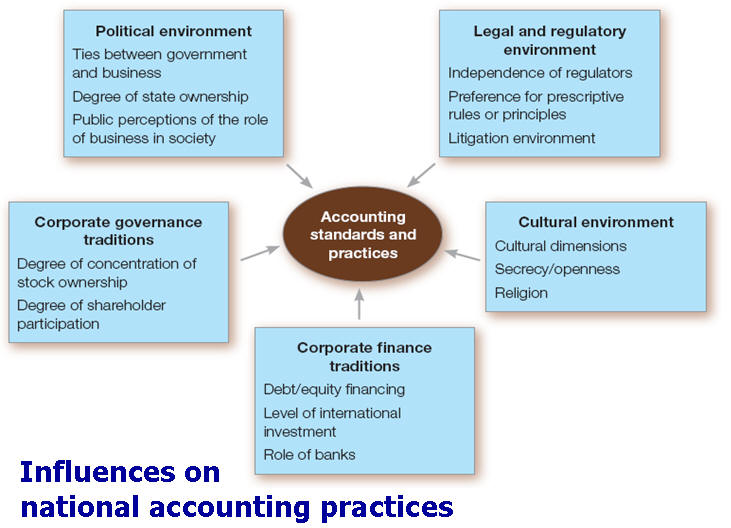

This is a broad question., which could constitute a written

assignment. The student could begin by summarizing the differences between

regulatory environments in contrasting countries. These would include an

advanced economy, an emerging economy and a developing economy. The advanced

economy will have a sounder, independent institutional environment.

Regulation in financial systems aims to assure those who carry out

transactions, and the investing public generally, that the system is fair

and transparent. If there is a financial scandal involving fraud and false

accounting, people blame not just the parties, but the regulators, for

failing to catch what was going on. Note that the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

introduced heavier criminal penalties. However, scandals can occur in any

country, shaking confidence in regulators.

If the cultural environment is one in which the rule of law

is widely respected, regulation is more effective than in an environment in

which players are constantly striving to get round the regulatory

requirements. A portion of players in any market will be in the latter

category. The section on this subject in the chapter highlights the weakness

of the legalistic approach to regulation, and suggests that a CSR approach,

which touches on values as well as forms, might help in the reform of the

regulatory environment.

A concern in emerging and developing economies is that

notions of independent regulators, not influenced by political and personal

ties, are not well established. Here, there is more scope for corruption,

even though the regulatory bodies and enforcement methods look, on the

surface, similar to those in countries with more robust institutions. The

strategic crossroads box on Indonesia highlighted that investors had been

welcome, but many suffered losses in the financial crisis, mainly due to the

weak financial and legal frameworks. Investing in Russia would entail

similar risks, with the addition of political intervention.

Hong Kong’s competitive advantages are at risk of erosion if

the mainland authorities decide to impose stricter controls in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s stock exchange is becoming more integrated with the mainland

economy as so many mainland companies are listing there (including

state-owned ones). Possibly paradoxically, if the mainland regime becomes

more open and transparent, Hong Kong’s competitive advantages could be

eroded.

As a SAR (special administrative region), Hong Kong was

assured some autonomy at the time of handover by the British to China in

1997. However, there is only limited democratic participation in the

election of the Legislative Council, and Beijing is essentially in control

of the process. There has been an active prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong.

The question touched on in the case study is whether Hong Kong needs

democracy to protect the rule of law. Most students would probably say that

it does, and that control from Beijing jeopardizes the rule of law. The rule

of law has been a key element in Hong Kong’s open economy. Tightening

control by Beijing would probably weaken the attractiveness of the SAR for

international investors.